How to Analyse an IPO Before Applying: A Step-by-Step DRHP Framework (2026)

- The IPO Most People Remember Wrong

- The Four Sections That Tell You Everything

- Follow the Money: Objects of the Issue

- What Could Break: Risk Factors

- Beyond the Numbers: The Quality Questions

- The Balance Sheet Traps

- The Price You Pay

- How to fix it:

- The Signals and The Process

- Before You Click Apply

- Frequently Asked Questions

The Draft Red Herring Prospectus runs hundreds of pages. Related-party transactions. Promoter salaries. Legal proceedings. Customer concentration. It's all there, buried between boilerplate and legalese.

Most retail investors skip it entirely. They check the grey market premium, read two analyst notes, and apply.

Then wonder why their allotment is underwater three months later.

This is a guide to reading IPOs like an analyst - starting with the DRHP sections that actually matter, moving to valuation math, and ending with the peer comparison that tells you whether the price makes any sense.

No jargon walls. No 400-page summaries. Just the framework that separates informed decisions from expensive guesses.

The IPO Most People Remember Wrong

November 2021. Paytm raised Rs 18,300 crore. India's largest IPO at the time.

The brand was inescapable. Blue QR codes at every kirana store. IPL title sponsorship. Sharma-ji using it to split dinner bills. The company had 330 million registered users. If India was going digital, Paytm was the face of it.

Listing day arrived. The stock opened at Rs 1,950 against an issue price of Rs 2,150. By close, it was down 27%.

Within a year, 70%+ of the value had evaporated.

The post-mortems were loud. Analysts blamed market conditions. Founders blamed timing. Retail investors blamed the bankers.

Read more: A Beginner's Guide to IPO Investing

But here's what nobody talked about.

The DRHP had said everything.

Page after page of disclosed losses. No clear path to profitability. A business model that burned cash acquiring users who generated little revenue. The valuation? 26-40x Price-to-Sales. At the same time, PayPal, profitable, global, established, traded at 10-15x. Visa and Mastercard, the ultimate payments franchises, sat at 20-24x.

Paytm wanted a higher multiple than the most profitable payments companies on earth. While losing money.

The OFS structure was right there too. Early investors, Alibaba's Ant Group, SoftBank, Elevation Capital, were selling. The people who knew the business best were using retail demand as their exit.

Macquarie published a 'sell' rating before listing. Called the valuation 'expensive’. The report was public.

Retail investors applied anyway. The IPO was oversubscribed 1.89 times.

That's the gap.

Not information access. The DRHP is free. SEBI mandates disclosure. Every risk factor, every related-party transaction, every loss statement, it's all there, published weeks before the bidding opens.

The gap is reading it. Knowing which sections matter. Understanding what the numbers actually mean.

Most investors checked two things: the grey market premium and what their WhatsApp group was saying. Both pointed up. Both were wrong.

This piece exists to close that gap.

Not with jargon. Not with 400-page summaries. Just the sections that matter, the math that reveals fair value, and the peer comparisons that show when the price makes no sense.

Four DRHP sections. Three financial statement checks. One valuation framework.

That's the toolkit.

The Four Sections That Tell You Everything

A DRHP for a mainboard IPO runs 400-500 pages. Sometimes more.

Nobody reads all of it. Not even the analysts getting paid.

Here's what they actually do: skip to four sections, spend two hours, and extract 80% of what matters. The rest is regulatory boilerplate, standard risk disclosures, legal definitions, compliance language that looks identical across every filing.

The four sections that separate useful IPO research from wasted time:

- Objects of the Issue. Where is the money going? Into the company's growth engine or into the pockets of promoters and early investors cashing out?

- Risk Factors. Not the generic ones about inflation and GDP growth. The top 15 company-specific risks that tell you what could actually break this business.

- Related Party Transactions. The character test. Is the promoter's ecosystem extracting value from the company you're about to own shares in?

- MD&A. Management Discussion and Analysis. Is revenue growth coming from selling more products or just raising prices? One compound. The other reverts.

That's it. Four sections. Maybe 50-60 pages of actual reading.

Everything else, the industry overview, the regulatory framework, the 47 pages of defined terms, exists because SEBI requires it.

The next four sections break down exactly what to look for in each. With examples of what good and bad actually look like.

Starting with where the money goes.

Follow the Money: Objects of the Issue

Every IPO raises money. The question is: for whom?

The 'Objects of the Issue' section answers this in black and white. It tells you exactly where every rupee is going. Capex. Debt repayment. Working capital. Or straight into the bank accounts of people selling their shares to you.

Two terms matter here.

- Fresh Issue - The company creates new shares. Money flows into the company's balance sheet. Fuel for growth.

- Offer for Sale (OFS) - Existing shareholders sell their stakes. Money flows out to promoters, PE funds, early investors. The company gets nothing.

Both are legal. Both are disclosed. But they mean very different things for what you are buying into.

Read more: Difference Between IPO and OFS

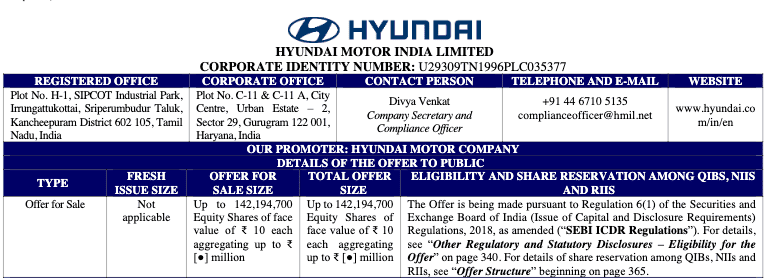

1. The Hyundai Problem

Source - SEBI

October 2024. Hyundai Motor India filed for the largest IPO in Indian history. Rs 27,870 crore.

The structure: 100% Offer for Sale.

Read that again. One hundred percent.

Every single rupee raised went to Hyundai Motor Company in South Korea. The Indian subsidiary, the entity whose shares would trade on NSE and BSE, the company you'd actually own a piece of, received nothing.

No capital for new plants. No funds for R&D. No debt reduction. No working capital boost.

The parent company in Seoul used Indian retail demand to cash out a portion of its stake. The Indian business entered the public markets with the same balance sheet it had before the IPO. Just with new shareholders who paid Rs 1,960 per share for the privilege.

The business risk transferred from Hyundai Korea to Indian public shareholders. The upside? Also transferred. But the capital to capture that upside? Still sitting in Seoul.

That's what a pure OFS looks like.

2. The IREDA Contrast

Source - SEBI

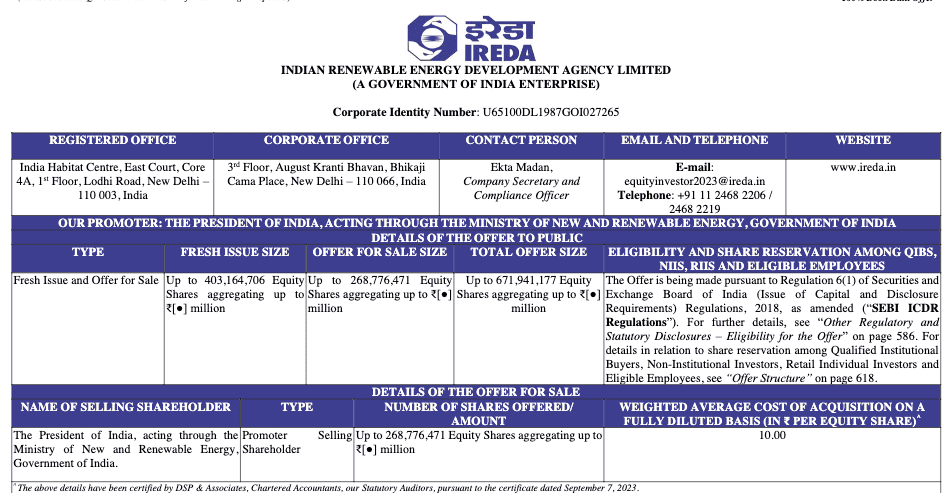

November 2023. Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency. Rs 2,150 crore IPO.

Different structure entirely.

Fresh Issue: Rs 1,290 crore. Sixty percent of the raise. Capital flowing directly into IREDA's books.

OFS: Rs 860 crore. Forty percent. Government of India reducing its stake from 100% to 75%.

The fresh issue proceeds? Earmarked to augment the company's capital base. IREDA is a lending institution. More capital means a bigger loan book. A bigger loan book means more interest income. More interest income means higher profits.

The IPO wasn't just changing ownership. It was funding growth.

The stock listed at a premium and kept climbing. Within months, it had doubled. Then tripled. IREDA became one of the standout performers of 2023-24.

The government got its partial exit. Investors got a company with actual capital to deploy. Everyone's incentives aligned.

That's what a balanced structure looks like.

3. The Tata Technologies Puzzle

Source - SEBI

Here's where it gets interesting.

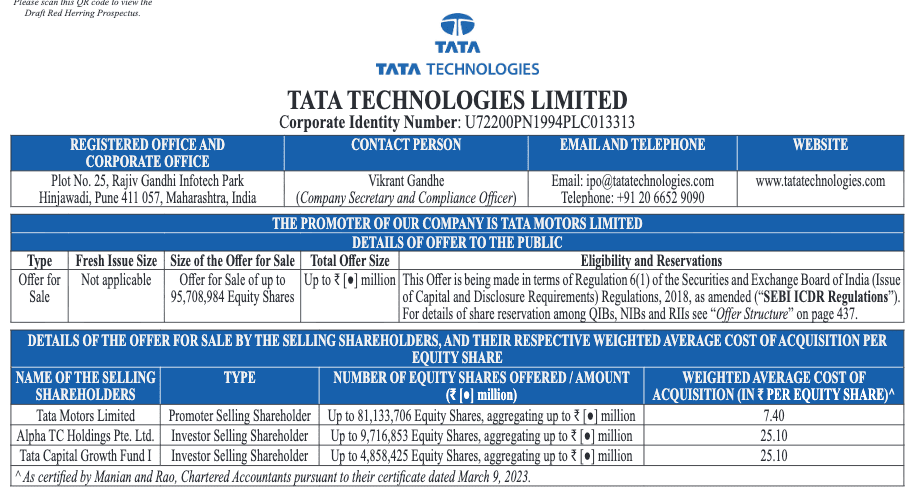

November 2023. Tata Technologies. Rs 3,042 crore. 100% OFS.

Same structure as Hyundai. The company received zero capital. All proceeds went to selling shareholders, Tata Motors, Alpha TC Holdings, Tata Capital Growth Fund.

And yet.

The stock is listed at 140% premium. Became one of the most celebrated IPOs in years.

How?

Valuation. Tata Tech was priced at ~32x P/E. Its direct peers, KPIT Technologies, Tata Elxsi, traded at 60-100x. The discount was so steep that investors didn't care about the OFS structure. They were getting a quality business at one-third the price of comparable companies.

The lesson: Structure matters. But it's not the only thing that matters.

A 100% OFS at a fair valuation can still work. A mixed structure at an absurd valuation will still destroy wealth.

Which brings us to what you're actually paying.

The OFS Question

High OFS isn't automatically a red flag.

Private equity funds have holding periods. They invest early, add value, and exit when the company goes public. That's the model. Warburg Pincus selling in an IPO is expected.

Founders taking some money off the table after a decade of building? Reasonable. They have concentration risk too.

The red flags are specific:

- Promoters significantly reducing stake at elevated valuations. If the people who know the business best are rushing to sell at the price being offered to you, ask why.

- 100% OFS with no fresh capital. The company's story is about growth. But the IPO doesn't fund any of it. You are buying the narrative. Someone else is taking the cash.

- Early investors fully exiting. When every PE fund and early backer is heading for the door simultaneously, they are seeing something you are not.

In Paytm's case, the OFS component was substantial. Ant Group reduced stake. SoftBank reduced stake. Elevation Capital reduced stake. The smart money that had funded Paytm's rise was using the IPO as an exit.

Retail investors became the exit liquidity.

The GCP Trap

Fresh Issue sounds good. But where exactly is the 'fresh' capital going?

SEBI allows companies to allocate up to 25% of their Fresh Issue proceeds to 'General Corporate Purposes’. GCP. A catch-all bucket for unspecified uses.

Some flexibility is reasonable. Business needs change. Opportunities emerge.

But when a company maxes out this 25% allocation and pairs it with vague language, 'brand building initiatives’, 'strategic investments’, 'inorganic growth opportunities', without naming a single specific target?

That's a company that doesn't have a concrete plan for your money.

What to check:

The DRHP includes a 'Deployment Schedule', a timeline for when the funds will be used. Vague timeline plus maxed GCP allocation equals weak capital planning.

Compare against specific disclosures.

Good DRHPs say things like: 'Rs 400 crore for new manufacturing facility in Gujarat, expected completion Q2 FY26.'

Bad ones say: 'Funds will be utilised for capacity expansion and general corporate purposes as the board deems fit’.

What Good Looks Like

A healthy Objects of the Issue section shows:

- Majority Fresh Issue (>50%). Capital actually entering the business you are investing in.

- Specific use of proceeds. Named projects. Quantified allocations. Clear deployment timelines.

- Debt reduction with math. 'Rs 600 crore to prepay high-cost term loans at 11.5% interest, resulting in annual interest savings of Rs 69 crore’. That's the impact on EPS you can calculate.

- Reasonable OFS with explained rationale. PE fund completing its investment cycle. Promoter diversifying personal wealth while retaining majority control. Logical reasons, not red flags.

- GCP well below 25%. Ideally under 15%. Shows the company knows exactly what it needs capital for.

What Could Break: Risk Factors

Every DRHP has a risk factors section. Every risk factors section is long. Forty pages. Fifty. Sometimes more.

Most of it is useless.

Generic warnings about inflation. Currency fluctuation. Regulatory changes. GDP slowdowns. Global recession possibilities. Geopolitical tensions.

They are disclaimers. Lawyers covering the company's back so nobody can sue later.

The actual risks, the ones that could crater this specific business, are buried in the first 10-15 points. Company-specific. Named. Quantified.

That's where you look.

Concentration Risk: The One Client Problem

Tata Technologies DRHP. Page after page of growth narrative. World-class engineering services. EV expertise. Aerospace contracts. Global delivery.

Then, in the risk factors: 72.75% of revenue comes from the top 5 clients.

And one of those top 5? Tata Motors. The promoter. The parent company.

Now think about what that means.

If Tata Motors decides to bring engineering services in-house, revenue hit. If Tata Motors faces its own slowdown and cuts vendor spending, revenue hit. If the relationship sours for any reason, revenue hit.

Seventy-three percent from five clients. One contract loss derails the growth. It's the most common way mid-cap companies blow up.

What to flag:

- >50% revenue from top 5 clients

- >25% revenue from a single client

- >40% revenue from a single geography or export market

A specialty chemicals company sending 80% of output to one European country. One EU regulatory shift. One tariff change. One trade policy update. The business model breaks overnight.

Concentration is an existential dependency.

Litigation: Routine vs Critical

Every company has legal disputes. Tax assessments. Commercial disagreements. Vendor conflicts. Employee matters.

Noise. Ignore it.

What you are looking for is different.

- Criminal proceedings against promoters. Not the company. The people running it. Fraud charges. Financial misconduct. Cheating cases. These don't settle quietly and follow the stock forever.

- SEBI actions. The market regulator investigating the company or its promoters. Disclosure violations. Insider trading inquiries. Price manipulation cases. When SEBI is involved, there's usually substance.

- RBI regulatory issues. For NBFCs, banks, financial services companies. License concerns. Compliance failures. Provisioning disputes. One adverse RBI order can shut down a lending business.

- Ongoing investigations by ED, CBI, or other agencies. Even if nothing is proven yet, the overhang suppresses valuation. Indefinitely.

The DRHP has to disclose all material litigation. Against the company. Against the promoters. Against group entities. Against directors.

Read it. If the promoter is fighting criminal charges while taking your money in an IPO maybe that's a reason to skip.

Contingent Liabilities: The Hidden Bombs

Balance sheets show what the company owes today. Contingent liabilities show what it might owe tomorrow.

Tax demands under appeal. Guarantees given to group companies. Legal claims where outcome is uncertain. Environmental liabilities pending assessment.

These don't hit the P&L until they crystallise. But they are real. And they are disclosed.

The check:

Find contingent liabilities in the notes to financial statements. Compare against net worth.

Contingent liabilities at Rs 500 crore. Net worth at Rs 600 crore. One adverse ruling and 80% of the equity base is wiped out.

That's a balance sheet with a time bomb.

High contingent liabilities relative to net worth means the company's financial strength might be illusory. The numbers look solid until they don't.

Related Party Guarantees

This one hides in plain sight.

The company has given guarantees on loans taken by promoter group entities. Or extended credit to sister concerns. Or advanced money to related parties.

If those entities default, the listed company is on the hook.

More than investing in this business. You are implicitly backing the promoter's entire ecosystem. Without seeing the books of those other entities. Without any say in how they are run.

Related party guarantees show up in contingent liabilities. They also show up in the Related Party Transactions section.

Cross-reference both. If the numbers are large relative to the company's own balance sheet, the risk is in everything the promoter touches.

The Regulatory Dependency

Some businesses exist because of government policy. PLI schemes. Export incentives. Tax holidays. Subsidised lending rates.

Not illegal. Not even problematic. India wants domestic manufacturing. The government is funding it.

But what happens when the scheme ends?

The DRHP should quantify this. How much of the margin comes from PLI benefits? What's the profitability without the subsidy? When does the scheme expire?

A company showing 18% EBITDA margin with 6% coming from government incentives has a real margin of 12%. The valuation should reflect that.

If the risk factors mention policy dependency but the projections assume incentives continue forever, that's a mismatch you are paying for.

What the Ordering Tells You

Risk factors are listed in order of materiality. SEBI requires it.

The first risk mentioned is the one management considers most significant. The second is next. And so on.

- If 'concentration risk' is point number one, management knows the client dependency is dangerous.

- If 'litigation' is in the top five, the legal matters aren't routine.

- If 'related party transactions' appear early, even the company acknowledges the governance questions.

Read the order the risks are placed.

The Risk That's Never Listed

One risk never appears in any DRHP: the promoter's intent.

Is this IPO a milestone in building a long-term public company? Or is it a liquidity event to cash out before the music stops? Via the document you will not understand, but some combination of signals will tell you.

High OFS with promoters selling aggressively. Vague use of proceeds. Concentrated customer base. Heavy related party transactions. Premium valuation despite all of the above.

That's an exit.

The risk factors tell you what could go wrong with the business. The rest of the DRHP tells you what might be wrong with the deal.

Read both.

Beyond the Numbers: The Quality Questions

Financial statements tell you what happened. Revenue went up. Margins expanded. Profit grew.

They don't tell you how it happened. Or whether it can happen again.

Two sections in the DRHP answer those questions. Most investors skip both.

- Related Party Transactions reveal who's really making money from this business. The company? Or the promoter's ecosystem?

- Management Discussion & Analysis reveals whether growth is real. Structural. Repeatable. Or just a cyclical blip dressed up as momentum.

One tests character. The other tests substance.

The Promoter's Other Businesses

Here's how value extraction works.

A company goes public. Thousands of shareholders. Quarterly scrutiny. Audit committees. Disclosures.

But the promoter also owns other businesses. Private companies. Family trusts. Partnership firms. No public shareholders. No scrutiny. No disclosures.

Now the listed company starts doing business with these private entities. Paying rent to a promoter-owned trust. Buying raw materials from a promoter-owned supplier. Giving contracts to a promoter-controlled vendor.

Every transaction moves money from the public company, where you own shares, to private entities, where you own nothing.

Legal? Usually.

In your interest? Rarely.

That's what Related Party Transactions reveal.

What Extraction Looks Like

The company leases its headquarters. Normal. Every company needs office space.

But the landlord is a trust controlled by the promoter's family. And the rent is 30% above market rate for similar properties in the area.

That 30% premium flows from public shareholders to the promoter's pocket. Every single month. Exposed in the DRHP. Ignored by most investors.

Or consider raw materials.

The company buys a key input from a supplier. Normal. Manufacturing needs inputs.

But the supplier is owned by the promoter's brother. And the pricing isn't benchmarked to the market. And the volumes keep growing even as alternative suppliers offer better rates.

Every inflated invoice is a transfer from public shareholders to the family.

The Red Flags

Open the Related Party Transactions section. Usually in the financial statements or a dedicated annexure.

Look for:

- Loans and advances to group companies. A listed tech company lending Rs 200 crore to a promoter's real estate venture. What's the business logic? There is none. That's capital being redirected.

- Guarantees for related party debt. The company guarantees a loan taken by a promoter entity. If that entity defaults, the listed company pays. You are backing businesses you can't see.

- Purchases from promoter-owned suppliers at unverified rates. No competitive bidding. No market benchmarking. Just money flowing to entities the promoter controls.

- Rent or service payments significantly above market. Office rent. Management fees. Brand usage charges. Consulting payments. All legitimate-sounding. All potential extraction channels.

- Sales to related parties at below-market prices. The company sells products to a promoter entity at a discount. That entity resells at full price. Margin shifted out of the public company.

The Arm's Length Illusion

Every DRHP says related party transactions are conducted at 'arm's length’. Auditors certify it. The board approves it.

Means nothing.

Arm's length certification is compliance. Minimum requirement. Checkbox.

It doesn't mean the transactions are in your interest. It means they're not blatantly illegal.

A promoter paying himself Rs 15 crore in annual rent for a property worth Rs 8 crore in rent can still get arm's length certification. The auditor confirms a transaction happened. Not that the pricing was fair. Not that alternatives were explored. Not that shareholders benefited.

Read the RPT section with skepticism. The certification protects the company from lawsuits. It doesn't protect you from value leakage.

The Pattern Matters

One related party transaction means nothing. Business ecosystems are complex. Promoters have multiple ventures. Some overlap makes sense.

But look for patterns.

RPTs growing faster than revenue. Every year, more money flowing to related parties even as the business scales.

RPTs across multiple categories. Rent AND raw materials AND loans AND guarantees. The entire promoter ecosystem feeding off the listed entity.

RPTs with entities that have no clear business purpose. A promoter's investment holding company receiving 'consulting fees.' For what consulting?

New RPTs appearing right before the IPO. Transactions structured specifically to extract value before public scrutiny begins.

Isolated transactions are noise. Patterns are signal.

Now the Other Quality Question

Related party transactions test whether the promoters are trustworthy.

The MD&A section tests whether the growth is trustworthy.

Revenue grew 40%. Impressive headline. But headlines lie.

The Management Discussion & Analysis breaks down that 40%. Where it came from. Why it happened. Whether it can continue.

This is where you separate structural growth from cyclical accidents.

Volume vs Value: The Only Question That Matters

Revenue can grow two ways.

- Volume growth. Selling more units. More customers. More orders. More market share.

- Value growth. Selling the same units at higher prices. Commodity cycle tailwinds. Inflation pass-through. Temporary pricing power.

One compounds. The other reverts.

A chemical company's revenue jumped 45% last year. The MD&A should tell you why.

Did they add new customers? Win contracts from competitors? Expand into new geographies? Build capacity that's now being utilized?

Or did benzene prices spike 60% and they simply passed it through?

The first story means next year could see another 30-40% growth. The second story means next year could see 25% decline when commodity prices normalize.

Same 45% growth. Completely different businesses.

Reading the MD&A

The section is usually 15-30 pages. Management's narrative on performance.

Look for:

- Volume data. Units sold. Customers added. Orders received. Capacity utilization. These are harder to fake than revenue.

- Price realization trends. Revenue per unit. Revenue per customer. Revenue per tonne. If this is rising faster than volume, growth is price-led.

- Market share claims. Backed by third-party data or self-reported? Crisil and ICRA reports carry weight. Management estimates don't.

- Capacity expansion details. New plants. New lines. New geographies. Growth requires investment. Is the company making it?

- Customer acquisition costs. Especially for consumer and tech businesses. If CAC is rising faster than revenue per customer, growth is being bought and is not organic.

The Margin Story

Revenue growth is vanity. Margin sustainability is sanity.

The MD&A explains margin movements. This is where you find out if profitability is real.

- EBITDA margin expanded 300 basis points. Great. But why?

- Operating leverage. Revenue grew faster than fixed costs. This sustains. As the company scales, margins should hold or improve.

- Input cost tailwind. Raw material prices fell. This reverts. When costs normalize, margins compress.

- Product mix shift. Sold more high-margin products. This depends. Is the shift structural or one-time?

- Discounting reduction. Sold at fuller prices. This is interesting. Suggests brand strength or reduced competition. Needs verification.

- PLI benefits. Government subsidies boosting margin. What happens when scheme ends?

The MD&A should tell this story. If it doesn't, if margin expansion is presented without explanation, that's a yellow flag. Management either doesn't understand their own business or doesn't want you to understand it.

The Compression Warning

Margin expansion gets celebrated. Margin compression gets buried.

But compression tells you more.

Revenue up 35%, EBITDA margin down 200 bps. The company grew but became less profitable doing it.

Possible reasons:

- Aggressive discounting to win market share. Common in new-age tech. Acquire customers now, figure out monetization later. Works until funding dries up.

- Input cost inflation with no pricing power. The company can't pass on cost increases. Customers will switch. This is a competitive weakness.

- Scaling inefficiencies. The company grew faster than its operations could handle. Execution problems. Management bandwidth constraints.

- Investment phase spending. Hiring ahead of revenue. Building infrastructure for future growth. Legitimate but needs runway clarity.

The MD&A should explain compression clearly. If management hides behind vague language, 'market dynamics,' 'competitive intensity,' 'strategic investments', they're either lying or clueless.

The Cash Conversion Check

Here's a quick quality test that combines both concerns.

Take EBITDA. The profit measure management loves because it excludes inconvenient things like depreciation and interest.

Now compare to Operating Cash Flow. The cash actually generated from running the business.

OCF should be at least 70% of EBITDA.

If it's not, something's wrong.

Revenue being recognized before cash is collected. Receivables building up because customers aren't paying. Inventory piling up because products aren't selling. Working capital consuming all the paper profits.

Low cash conversion is either:

- Aggressive accounting. Booking revenue that isn't real yet. This unwinds badly.

- Business model weakness. The company can't collect what it's owed. Customers have the power.

- Channel stuffing. Pushing inventory to distributors to inflate pre-IPO numbers. This definitely unwinds badly.

EBITDA is an opinion. Cash flow is a fact. When they diverge significantly, trust the cash.

The Combined Quality Framework

Before finishing with the DRHP's qualitative sections, run this check:

Two red flags in governance? The promoter may not be aligned with you.

Two red flags in growth quality? The numbers may not repeat.

Both? Find another IPO.

Read more: Different Types of IPO

The Balance Sheet Traps

Income statement gets all the attention. Revenue growth. Margin expansion. Profit jump.

The balance sheet is where companies hide the mess.

Receivables Creep

Revenue grew 35%. Receivables grew 60%.

That's definitely not growth.

When receivables grow faster than revenue, one of two things is happening.

- Customers aren't paying. The company booked sales but can't collect. Those receivables will eventually become write-offs.

- Channel stuffing. The company pushed inventory to distributors on credit to inflate pre-IPO numbers. Looks like sales. Isn't really demand.

Both unwind badly. Usually within two quarters of listing.

The check: Calculate receivable days. Compare across three years. If it's increasing while revenue grows, the growth is partially fake.

Inventory Bloat

Same logic. Different line item.

Revenue up 40%. Inventory up 80%.

Either demand projections were wrong and products aren't selling. Or the company built stock specifically to show 'readiness for growth' before the IPO.

High inventory ties up cash. It also risks obsolescence. And write-downs.

The check: Inventory days trending up while the company claims demand is strong? Mismatch. Something's off.

The Debt Cost Signal

Debt-to-equity is standard. Everyone checks it.

Cost of debt is better. Fewer people look.

If a company borrows at 14% when peers borrow at 10%, lenders see higher risk. They know something. Credit rating agencies know something.

Many IPOs use proceeds to retire high-cost debt. Good use of capital. But calculate the real impact.

Rs 500 crore debt at 14% = Rs 70 crore annual interest. Retire it, and that's Rs 70 crore flowing to profit. At 25% tax rate, that's Rs 52 crore additional PAT.

That's the EPS boost baked into 'post-IPO projections.' Make sure it's real, not double-counted.

The Working Capital Equation

One formula tells you how efficiently the business runs:

Working Capital Cycle = Receivable Days + Inventory Days − Payable Days

Lower is better. Negative is best (for consumer businesses).

If this number is rising year-over-year, the company needs more cash to run the same business. Growth will consume capital instead of generating it.

Compare against peers in the same sector. A company with 90-day working capital cycle competing against peers at 45 days has a structural disadvantage. It needs twice the capital to operate.

Three checks. Fifteen minutes. Tells you if the balance sheet supports the income statement story, or contradicts it.

The Price You Pay

Valuation is a question: What are you paying for what you're getting?

The answer changes by sector.

The Metric That Matches

Profitable companies: P/E ratio. What you pay per rupee of earnings. Nifty 50 average sits around 22-23x. Pharma trades at 33x. IT services at 25-30x. FMCG at 40x+.

An IPO priced at 45x P/E isn't expensive if the sector trades at 50x. It's expensive if the sector trades at 25x.

Banks and NBFCs: P/B ratio. Book value is the anchor. HDFC Bank commands 3x+ because of ROA and asset quality. PSU banks trade at 1x or below. An NBFC IPO at 2.5x book needs HDFC-like metrics to justify it.

Infrastructure, telecom, cement: EV/EBITDA. Capital-intensive businesses with heavy depreciation. P/E gets distorted. EV/EBITDA strips out capital structure noise. Infra typically trades at 9-12x.

Loss-making tech: Price-to-Sales. The danger zone. No profits means no P/E. So bankers use revenue multiples. This is where Paytm happened. Where most retail wealth destruction happens.

P/S above 10x for an unprofitable company requires near-perfection in execution. Above 20x requires delusion.

The Peer Trap

Every DRHP has a peer comparison table. Every table is misleading.

Companies pick flattering comparisons. A regional logistics player lists itself against Delhivery. A small NBFC appears next to Bajaj Finance. A niche IT firm benchmarks to TCS.

The valuation looks cheap. Of course it does. That's the point.

How to fix it:

Match business models first. Revenue size second. Growth stage third.

A Rs 500 crore revenue company doesn't compete with a Rs 50,000 crore giant. Their valuations shouldn't be compared either. Smaller companies trade at structural discounts, lower liquidity, higher risk, less analyst coverage.

Find peers yourself. Screener.in lets you filter by sector, revenue range, and margins. Tijori Finance shows operational metrics, order books, ARPU, capacity utilization.

Fifteen minutes of independent peer research beats whatever the investment banker put in the DRHP.

Read more: 5 Momentum Stock Screener Strategies

The Cheap Trap

LIC IPO. May 2022. Priced at 1.1x embedded value.

Private insurers, HDFC Life, SBI Life, ICICI Pru, traded at 2.5-3.9x embedded value. LIC was offering a 70% discount to the sector average.

Screaming buy. Obvious value.

Except.

LIC's value of new business margin was 9.3%. Private peers operated at 20%+. The product mix was wrong, 99% non-linked traditional products while customers were shifting to ULIPs that private players offered. Government ownership meant constraints on compensation, strategy, and agility.

The 'discount' was the market pricing in structural disadvantages.

The stock listed at Rs 867, below the Rs 949 issue price. By February 2023, it hit a record low of Rs 568. Fourteen months after listing, shares still traded 33% below issue price.

Cheap relative to peers means nothing if the business is structurally weaker than peers.

Low valuation can mean undervaluation. It can also mean the market sees something you don't.

Before celebrating a 'discount,' ask why it exists.

The One Calculation

PEG ratio. Price/Earnings divided by Earnings Growth Rate.

A company trading at 40x P/E growing at 40% annually: PEG of 1.0.

A company trading at 20x P/E growing at 10% annually: PEG of 2.0.

The 'cheaper' P/E is actually more expensive relative to growth.

PEG below 1.0 suggests undervaluation. PEG above 2.0 suggests you're overpaying for the growth on offer.

Simple filter. Eliminates half the IPOs that look cheap but aren't.

Valuation is relative. To the sector. To the peers. To the growth. Get any comparison wrong, and you'll pay the right price for the wrong business.

Read more: What is the PE Ratio?

The Signals and The Process

Grey market premium. The number everyone checks. The number that means almost nothing.

GMP is the unofficial price at which IPO shares trade before listing. High GMP supposedly predicts listing gains. Low GMP warns of tepid debuts.

In 2024-25, this correlation broke.

Multiple IPOs with strong GMPs listed flat or negative. The grey market is thin, manipulable, and increasingly disconnected from institutional sentiment. Operators can inflate GMP to create FOMO. By the time retail notices, the smart money has already decided.

The signal that actually matters: QIB subscription.

Qualified Institutional Buyers, mutual funds, insurance companies, FIIs, do real due diligence. They meet management. They build models. They negotiate allocations.

When QIBs oversubscribe 50x on the final day, it means institutions validated the price. When QIBs barely show up but retail oversubscribes 10x, the informed money is staying away while the uninformed pile in.

High retail + low QIB = hype without substance. That's your warning.

The Anchor Book Shortcut

One day before the IPO opens, companies announce their anchor investors. This list is gold.

Quality anchors: SBI Mutual Fund. HDFC MF. ICICI Pru. Government of Singapore (GIC). Fidelity. Capital Group. These names invest for 12-36 month horizons.

Weak anchors: Small funds you've never heard of. Short-term trading desks. Names that appear in every anchor book regardless of quality.

Full anchor subscription by reputable long-only funds means two things. One, professionals validated the valuation. Two, the 30-90 day lock-in creates post-listing stability.

If the anchor book is weak or undersubscribed, that's institutions voting with their absence.

The Timeline

1. T-10 (Announcement)

DRHP goes public. Download it. Check three things immediately:

- Fresh Issue vs OFS ratio

- Promoter holding before and after

- Top 5 client concentration in risk factors

Ten minutes. Decides whether you keep reading.

2. T-3 (Price Band)

Calculate valuation at the upper band only. Lower band is irrelevant, allotments happen at cut-off price.

Pull up Screener.in. Find 3-4 listed peers. Compare P/E, P/B, or EV/EBITDA depending on sector.

IPO priced above peers? Need exceptional growth to justify it. Priced below? Ask why, discount or trap?

3. T-1 (Anchor Book)

Check the anchor investor list. Quality matters more than quantity.

Reputable names with long holding periods = validation. Weak names or partial subscription = caution.

3. Day 2 of Bidding

Don't apply on Day 1. Wait.

Check QIB subscription by Day 2 afternoon. If institutions aren't showing up, reconsider.

Retail oversubscription alone means nothing. Retail chased Paytm too.

4. Application

UPI for ASBA. Funds stay in your account until allotment.

One lot per family member. Multiple lots in a single name don't improve odds, retail allotment is lottery-based when oversubscribed.

The Sequence

DRHP filters out the obvious problems.

Valuation filters out the overpriced.

Anchor book filters out the institutionally rejected.

QIB subscription confirms or contradicts your thesis.

Skip any step, and you're guessing. Follow all four, and you're still not guaranteed returns, but you've eliminated the avoidable mistakes.

Before You Click Apply

Four questions. Each one is a gate.

Fail any gate, and the odds shift against you. So basically, the margin of safety disappears.

One: Where does the money go?

Fresh Issue means capital enters the company. Growth gets funded.

High OFS means capital exits to promoters and early investors. You're the liquidity.

Hyundai was 100% OFS. Rs 27,870 crore to South Korea. Zero to the Indian business.

The filter: If OFS dominates and promoters are selling aggressively at peak valuations, who knows more about this business, them or you?

Two: What could break it?

Concentration. Litigation. Contingent liabilities.

50% revenue from five clients is dependency, we can’t call it diversification. Criminal cases against promoters don't disappear after listing. Contingent liabilities exceeding 30% of net worth mean the balance sheet is one court ruling from collapse.

The filter: Would you start a business with this customer concentration, these legal risks, these hidden liabilities? No? Then why buy shares in one?

Three: Is the price fair?

Not cheap. Fair.

LIC was cheap, 1.1x embedded value versus 3x for peers. Still destroyed wealth. The discount reflected structural weakness, not opportunity.

Tata Tech was expensive in absolute terms, Rs 500 per share. But at 32x P/E versus peers at 80x, it was the cheapest quality asset in its sector.

The filter: Compared to similar businesses, are you paying less for equal or better fundamentals? If you're paying more, what justifies the premium?

Four: Who else is buying?

Anchor book filled with SBI MF, HDFC MF, GIC, institutions who hold for years, not days.

Or anchor book filled with names you've never heard of, funds that flip on listing day.

QIB subscription 50x means the informed money validated the price. QIB subscription 2x while retail goes 15x means you're the exit.

The filter: If professionals who analyse IPOs full-time aren't showing up, what do you know that they don't?

Four questions. Four gates.

Pass all four, and apply. Fail one, and demand a bigger discount. Fail two, wait for listing, buy later if the business proves itself.

Fail three or more? There are 50+ IPOs a year. Find a better one.

Soo… What the DRHP Told You All Along?

Paytm's 26x Price-to-Sales. In the filing.

LIC's 9% VNB margin versus 20% for peers. In the filing.

Hyundai's 100% OFS with zero capital to India. In the filing.

Tata Tech's 32x P/E when peers traded at 80x. In the filing.

The documents that predict IPO outcomes are published weeks before you bid. Free. Public. Ignored.

But here's what we haven't covered.

The SME IPO frenzy. 2024 saw 243 companies list on SME exchanges. HOAC Foods raised Rs 5.5 crore and received Rs 11,000 crore in bids, nearly 2,000x oversubscribed. Kay Cee Energy's Rs 15.9 crore issue attracted Rs 16,500 crore. Stocks listing at 300-400% premiums.

SEBI flagged concerns. 'We do see signs of manipulation in the SME segment,' the chairperson said publicly.

Some are legitimate small businesses accessing public markets. Some are setups dressed as growth stories. Same framework applies. Different red flags to watch.

That's the next piece.

Meanwhile, the mainboard pipeline is live. New filings drop every week. Track upcoming IPOs, access DRHPs, compare peer valuations, and read detailed analyses.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How to get 100% IPO allotment?

You can't guarantee allotment. The retail category uses lottery when oversubscribed. But you can improve odds: apply for one lot per family member instead of multiple lots in one name. Apply at cut-off price, not lower band. Use ASBA via UPI, failed mandates mean rejected applications. For HNI category, small HNI (Rs 2-10 lakh) is also lottery-based now.

2. What is a good PE ratio for IPO?

Depends on sector. Compare against listed peers, not Nifty average. Pharma trades at ~33x, IT services at 25-30x, FMCG at 40x+. Tata Tech at 32x looked expensive until you saw peers at 80x. Also check PEG ratio (P/E divided by growth rate), below 1.0 suggests undervaluation.

3. What is the 30 day rule for IPO?

Anchor investors face a 30-day lock-in on 50% of their allotted shares (remaining 50% locked for 90 days). This prevents institutions from dumping shares on listing day. Quality anchor books with long-term funds (SBI MF, HDFC MF, GIC) signal price stability post-listing.

4. How to know if an IPO is overpriced?

Compare P/E or P/S against peers in same sector. Paytm at 26-40x Price-to-Sales was overpriced because profitable PayPal traded at 10-15x. Check if growth justifies premium. High valuation + 100% OFS + weak anchor book = likely overpriced.

5. How to analyse IPO prospectus?

Focus on four sections only: Objects of Issue (where money goes), Risk Factors (top 15 company-specific), Related Party Transactions (governance check), MD&A (growth quality). Skip the 300 pages of legal boilerplate. Check restated financials for revenue vs profit CAGR divergence.

6. Which IPO analysis website is best?

Chittorgarh.com for subscription data and allotment stats. Screener.in for peer comparison and custom ratios. Tijori Finance for sector-specific operational metrics. SEBI website for official DRHP filings. Track upcoming IPOs and detailed analysis at Research 360 IPO section.

- The IPO Most People Remember Wrong

- The Four Sections That Tell You Everything

- Follow the Money: Objects of the Issue

- What Could Break: Risk Factors

- Beyond the Numbers: The Quality Questions

- The Balance Sheet Traps

- The Price You Pay

- How to fix it:

- The Signals and The Process

- Before You Click Apply

- Frequently Asked Questions